Every year, the Procession has a theme. We talked about 2015’s theme of UnMournable Bodies in a previous post—those people who our culture doesn’t consider worthy of public mourning. The ones we forget, turn away from, or are repulsed by.

The Ambassadors—the group that offers paper and pencil to people in the street during the Procession so that they can write a message to place in the Urn—has a special assignment for their costumes this year. They are remembering the Forgotten Ghosts of the Road, the people who have labored to build our country, the slaves, convict laborers, braceros, farm workers, miners, child workers, Chinese railroad workers, all the different populations who have built the streets we walk on, the food we eat, the monuments in our nation’s capitol, the railroad tracks that bring our food and goods to us.

During the Finale Ceremony, the Ambassadors will place their tunics into the Urn to burn in honor of these ghosts. The rope trim on the tunics represents labor—rope as a tool for getting work done—and bondage. The brightly colored patterns represent the work—the road, the railway, the paths created. Each Ambassador has taken a different approach, found their own way to represent these ghosts on their costumes and in their hearts during the Procession. There are 15 Ambassadors for the Procession this year. Here are a few of their stories.

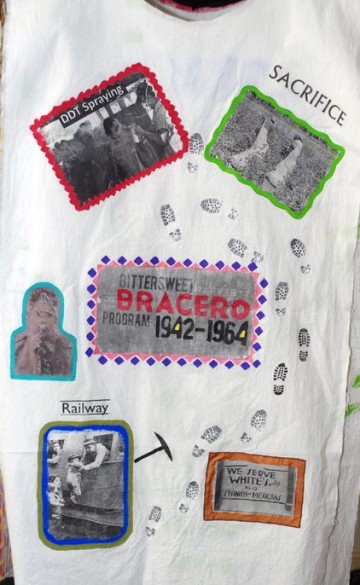

Lupe Lopez: Braceros

“This is the story of my father, Ramiro, who was born in April 1925 and from 1944 to early 1960s was a part of the Bracero program. Braceros were Mexican workers brought to the United States during World War II to work the fields and do the labor that had been done by men who were now serving in the war. When the seasonal work was over they were sent back to Mexico the same way they were brought in, by train.

When my dad was 19 years old, married with his first son only 3 months old, he had to leave his family behind to come to the USA to work. When they reached the USA border they were stripped down to nothing and people sprayed their hair and their private parts with DDT (insecticide) to avoid them bringing any bugs to the USA. This happened every time he returned to the USA to work.

My dad worked primarily in California picking cotton. That was hard work because they had long bags that they carried across their chest and dragged across the fields filling them up with cotton. They weighed so much that it was very tiring. Another time he worked cutting ice. He was taken to a frozen lake and workers had to cut large cubes of ice. My dad always blamed that job for his problems with arthritis, because he said it was so cold that he could feel the cold go through his work boots and socks. Some of the men that worked with him ended up getting their ears cut off because their earlobes had frozen from the cold weather.

In the late 1960s, my father worked in the fields in Yuma, Arizona picking lemons, oranges, grapefruit, etc. He would save enough money to apply for residency for 2 to 3 family members at a time. In 1978, my dad was able to get permits for the four youngest of the 13 children. My sister and I (8 and 11 years old) were given permission to attend school, but my brothers at the age of 13 and 15 were given work permits. They had to start working on the fields just like the rest of the family. Life went on, and even with all our struggles as a family we managed to survive and find a better life for all of us here in the United States. My father passed away after 89 years of life in January 2014.”

Lupe’s costume is decorated on the front with photographs of her father, Ramiro, from different phases of his life. The tree is railroad tracks, and each branch represents a trip he made to to the USA to work. On the back of the tunic, she has photographs of Braceros being sprayed with DDT, saying goodbye to their children as they board a train for the USA, hauling cotton bags through fields. And a “We serve Whites only. No Spanish-Mexicans” sign.

Melanie Cooley: Convict Leasing

Melanie Cooley: Convict Leasing

“As the descendant of a white Southern family, it was the enslavement of African Americans that drew my focus. My family is from Tennessee, from South and North Carolina. And in digging through our genealogical records, we’ve found at least one will where my ancestor left ‘1 Negro male’ to his descendants. We weren’t big plantation owners, but the history of slavery in this country is our history.

As I researched, one photograph in particular drew my attention: a boy, hogtied in the middle of a dirt lot, wooden shacks behind him. It seemed too contemporary to be a slavery-era photograph, and I wanted to check that it wasn’t a still from a movie. A Google image search revealed that it was a photograph of a boy in a prison camp in the 1930s. That’s why it looked too modern. And as I continued to research, I learned just how smoothly slavery segued into convict leasing, into a system of forced labor that in some cases was even more brutal than legal slavery. Convicts—mostly African American men—were literally worked to death building roads and railroads and working in mines. The documentary Slavery by Another Name was a heartbreaking revelation. It’s not an exaggeration to say that convict leasing allowed enslavement of African Americans to extend well into the 20th century. And it laid the groundwork for the prison system we have today.

The color patterns on my tunic are tire treads. Most of the photographs are of convicts from the convict leasing era, many of whom were imprisoned for minor offenses like loitering or vagrancy, or of African American slaves. On the sides of my tunic are ledgers of deaths from prisons practicing convict leasing. The lists in those ledgers are long. The death rate was astronomical. I have names—Ernest Thomas, killed trying to escape; Fate Taylor, killed by log train; Homer Williams, overheated, and thousands more. I have faces. But nowhere have I found names paired with faces.”

Rita Schmidt: The Civilian Conservation Corps

“I wanted a topic that was relevant to my ancestors, white-collar city workers as far back as we know. In particular, those who lived through the Great Depression and the attendant sense of helpless, loss and dispossession. Since my family loves to hike and camp, I originally thought of the Works Projects Administration because I knew they built the Hoover Dam and one of my family’s favorite hiking trails. But I found a photo of Native American youths working on a Civilian Conservation Corps project in Arizona. Since the CCC involved young men from the Depression and was exclusively devoted to forestry and the infrastructure of parks, it seemed perfect. I also found a book of photos called The Civilian Conservation Corps in Arizona.

What I like about the CCC is that even though the people involved were unmournable bodies in a way—hungry, unemployed, and without opportunities, including Southern black men and Native Americans—they were brought together for a common purpose and treated well. Safety was emphasized and there were no deaths in Arizona and few injuries. Many of them said that the CCC literally saved their life. The CCC in a way took advantage of the awful situation created by the Depression of so many hungry and unemployed people and used them to create the infrastructure of our public parks.”

Photographs of the Civilian Conservation Corps working on Arizona projects—including Randolph Park and Saguaro National Park—are on Rita’s tunic that she will wear in the Procession.